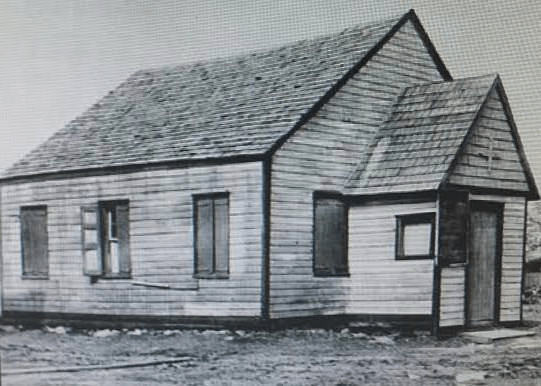

The first church building of the United African Church. A cemetery was built behind the building, which was recently rediscovered. (Courtesy of Elmhurst Histories and Cemeteries Preservation Society)

Nov. 12, 2018 By Meghan Sackman

A local group dedicated to preserving Elmhurst history is working to landmark a recently discovered African burial ground in the area that is in the midst of potentially being developed.

The Elmhurst Histories and Cemeteries Preservation Society filed an application with the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission last month formally asking the agency to evaluate the property at 47-11 90th St. for landmark status, given its history as a burial ground for freed African Americans.

While the burial ground and surrounding property maintain a rich history, the burial ground at the site was only re-discovered seven years ago, when construction workers began to excavate the lot for development and instead struck an iron coffin with the body of a woman inside.

The well-preserved body led many to initially believe that the woman had been the victim of a recent crime. But further investigation led to the astounding revelation that the site was not empty as once thought, but was instead a burial ground for formerly enslaved African Americans since the early 1800s.

The body found in the coffin was identified as that of Martha Peterson, an ex-slave, and researchers estimate that 300 bodies are currently buried there.

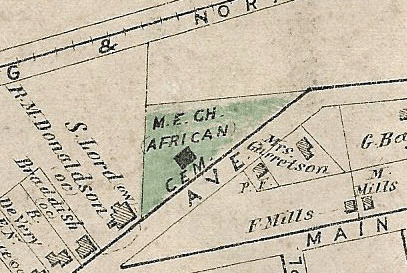

The African burial site as seen from above, near Corona Avenue and 91st Place. While stores and homes rose in adjacent parcels, the burial ground has remarkably remained undeveloped. ((Courtesy of Elmhurst Histories and Cemeteries Preservation Society)

Although the developer, Song Liu, is currently unable to build on the site because of an archaeological restriction placed shortly after the cemetery was rediscovered, Liu filed plans in September to build a five-story, 80-unit building with a ground floor museum on top of the site.

Now, the group’s landmarks application is an effort to stop any development on the site—period—and instead honor it for what it once was.

“To have an African American burial ground from one of the first freed cities definitely needs recognition, preservation and respect, because up until now it’s been mistreated and forcefully forgotten,” said Marialena Giampino, president of the Elmhurst History and Cemeteries Preservation Society.

The property, according to the group, was purchased by four formerly enslaved men in 1828 shortly after they were granted their freedom. Elmhurst, previously called New Town, was one of the first municipalities in New York State to liberate slaves.

1859 detail of a map of Newtown, displaying the presence of the African Cemetery and a chapel building (via Elmhurst Histories and Cemeteries Preservation Society)

The liberated peoples formed the United African Society, and then built what would later be known as the African Methodist Episcopal Church with a cemetery behind it right on the property, according to James Ng, treasurer of the Elmhurst Histories and Cemeteries group.

In 1928, the landowners decided to sell the property after the city widened Corona Avenue and the area began to develop. The church was knocked down shortly after its sale, while store upon store began to be built Corona Ave and 90th Street, but not directly on top of the burial site.

Upon selling the property, the congregation found a new place to worship in Corona. Decades later, and after two additional moves and splintered factions, the descendants of this group hold services at St. Mark’s American Methodist Episcopal Church at 95-18 Northern Blvd.

The records of what happened to the physical church on 90th Street as well as the cemetery are sparse, given the city’s decision to de-map the burial ground in the 1930s and the lack of effort to record and preserve its history, according to the group.

Since then, the land has had several owners, including Peerless Instruments, a company that sold airplane parts to the government. The documentation showing the chain of ownership on the land, however, is incomplete.

The current developer purchased the site in 2011, the same year that the lot’s history was uncovered.

Since the rediscovery, the existing congregation at Saint Mark’s has been in a legal battle with the developer due the remains found in the cemetery belonging to the church, Giampino said.

The church, which was not available to comment, has sought ownership of the artifacts and bodies in the ground.

Liu, meanwhile, declined to comment for this story.

James McMenamin, vice president of the Elmhurst History and Cemeteries Preservation Society, said his group is now waiting to hear back from Landmarks following its request for evaluation.

McMenamin also aims to get local politicians on board to preserve the site and keep raising awareness of the issue.

“I’d love to see it turned into a landmark with free access for people, maybe a shrine or a museum for recognition of African Americans’ contributions to New Town’s history,” McMenamin said.

“We’ve seen so much history lost; a lot of newer people don’t seem to appreciate or realize what’s been here,” he added. “We are just scared that another disastrous ending could happen.”

One Comment

I have walked past there a million times. I never knew there was a cemetery there. May all it’s inhabitants know peace