A construction site on Kent Avenue in Williamsburg, May 16, 2022.Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

This article was originally published by The CITY on May 19

The clock is ticking on the final days of a likely-to-expire tax break real estate developers rely on to build new apartments — and the rush is on to get foundations in the ground before June 15, when 421-a will end unless the state legislature passes an extension.

In Astoria, Queens, the second phase of the Durst Organization’s massive Hallett’s Point development will have laid all its foundations by the middle of next month — allowing those buildings to qualify for the lucrative property tax incentive. But Phase 3 and its 800 more apartments will be shelved if 421-a expires, says the developer.

“The only place we could build a market rate apartment building without 421-a is near Union Square or maybe in a few other slices of Manhattan,” said Jordan Barowitz, a company vice-president.

In Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Two Trees Management Co. has begun constructing 350 Kent as part of its equally massive Domino development, which will add 400 units — 30 percent of them designated as affordable, or rented to households earning specific incomes, under the city’s inclusionary housing program.

But a rep for the developer says the future is “cloudy” for another planned building at Domino and the first two structures planned at its newly approved River Ring site because they may not be able to pour their foundations before the deadline.

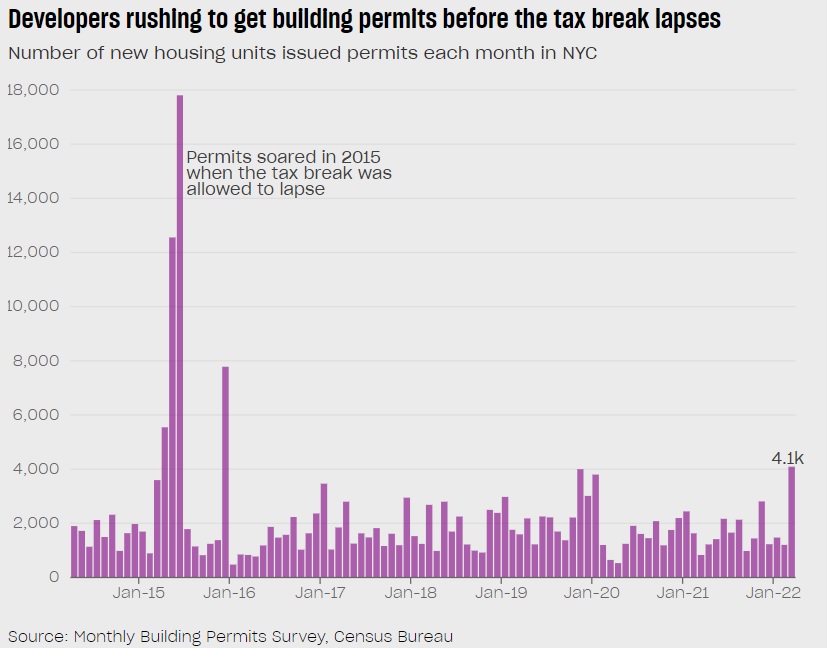

New units issued permits soared to 4,091 in March, according to Census Bureau’s building permits survey data analyzed by THE CITY, compared with 2,678 in January and February combined. Sources who have seen preliminary data for April and early May say the surge has continued.

SUHAIL BHAT / THE CITY

Developers say that much needed housing construction — especially of income-restricted affordable apartments now required in return for the incentive — will come to a screeching halt after 421-a expires for any sites that haven’t started by June 15.

Buildings qualifying for the 421-a tax break must set aside 25 percent to 30 percent of their units for affordable housing at specified family income levels. About 90 percent of all residential construction in the city in the last decade received either 421-a or other tax breaks, according to the NYU Furman Center. Half of all affordable apartments since 2014 were built under 421-a, according to city data.

Even as developers rush to beat the deadline and claim the credit, critics are saying good riddance to the tax break, which costs the city $1.8 billion a year by eliminating or reducing property taxes for up to 35 years.

Those who seek to end the program contend that a lapse will have no immediate effect and that there are other ways to make building rental housing economically attractive.

Yet even as the 421-a program expires, there will be no windfall for the city, since buildings that qualify before the cut-off will continue to receive the benefit for as long as three decades. The nonprofit Citizens Budget Commission estimates the end of 421-a will bring in less than $100 million annually over the next seven years.

Affordable Housing Shortage

Mayor Eric Adams made one more push to renew the tax break on his trip to Albany earlier this week and said he hoped there could be an agreement on some replacement for 421-a. But insiders say the odds are against anything but a short-term extension.

The 421-a controversy comes amid an ever-worsening housing crisis. Earlier this week, the city’s latest official Housing and Vacancy Survey showed a historically low vacancy rate of 1 percent for affordable apartments.

New York needs 560,000 new units of housing by 2030 to make up the deficit in new construction over the past decade and accommodate expected population and job growth in the post-pandemic city, according to a study released earlier this year by the consulting firm AKRF commissioned by the Real Estate Board of New York.

The permit scramble happening now is a repeat of 2015, in the months leading up to a lapse of the tax break in a fight over whether buildings would be required to pay higher construction wages. The number of new units issued permits that year soared to more than 55,000 from 20,000 the year before.

Permits then plunged to 15,000 in 2016 before the program was reinstated at the end of the year, then slowly increased.

Affordable housing advocates marched through Lower Manhattan, demanding an end to 421-a tax breaks and the passage of a pro-tenant law, April 21, 2022.Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

When the tax break expired back then, Durst immediately stopped work on Hallett’s Point after completing one 400-unit building — leaving the rest of the project’s planned 2,000 apartments, almost 500 of which would be affordable, in limbo. When the tax break was reinstated the following year, work resumed.

With Phase 2 in the ground, Durst will be able to complete 1,600 units. But the remaining 800 won’t be built without the tax break.

“Without 421-a or a comparable tax incentive, the economics of the third phase of Hallett’s are not viable,” Barowitz said.

Rentals in New York pay much higher property taxes than other kinds of housing, eating up as much as 30 percent of all rental income. Condos, co-ops and single-family homes pay much less.

Other developers are switching their plans from rental to condos, says Patrick Sullivan, a partner at the law firm Kramer Levin, who adds that not one of his clients plan to proceed with a rental building after 421-a expires.

The only exception will be projects where zoning approval was tied to a percentage of affordable units under the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program. In that case, his clients will attempt to build two buildings, one with condos and the other with affordable apartments that can qualify for other tax breaks.

Because developers will beat the June 15 deadline, the impact won’t be felt immediately.

“There will be a four or five-year lag until the lack of building shows up,” said David Lombino, managing director at Two Trees.

Inaction to Spur Action

Opponents of 421-a, including the city’s chief financial officer, dismiss the developers’ claims.

“The Department of Buildings permitted more units so far in 2022 than they had by this time last year, and we expect permits will continue to climb as we near the 421-a expiration date. Housing development will not come to a crashing halt in a month,” said Comptroller Brad Lander.

Lander has been campaigning for property tax reform that equalizes the burden for rental units and eliminating 421-a. The lower tax burden would be sufficient to spur housing construction at a lower cost to the city, he says.

The Community Service Society, another 421-a opponent, supports the Lander approach. But the 179-year-old nonprofit also argues that ending 421-a will lead to lower land costs which will translate into less expensive housing.

“It is possible that the lapse of 421-a would effect some adjustments in the immediate future, but we firmly believe that ending 421-a would ultimately encourage the construction of more housing in the long term by stopping the inflationary cycle around land value and rents,” said senior economist Debipriya Chatterjee.

The property tax break is governed by state legislation. Gov. Kathy Hochul proposed a revised tax break as part of her budget, with tougher affordable housing requirements, but didn’t demand a reluctant legislature approve it in the final budget negotiations. Mayor Eric Adams sought to convince legislators to renew the tax break during his lobbying trip to Albany this week.

Insiders say there is a slim chance the legislature will agree to a short-term extension — but add that a long-term renewal is off the table, as primaries for their seats loom over the summer. Both the Adams administration and real estate interests are expected to lobby to reinstate the tax break after the elections are over.

“Albany’s inaction will only worsen the city’s housing crisis,” said James Whelan, president of the Real Estate Board of New York. “The question moving forward is how bad does that crisis need to get for New Yorkers before elected officials address the issue through sound, fact-based policies rather than fringe, Twitter-friendly rhetoric.”