(Lucas Klappas via Flickr)

May 14, 2019 By Christian Murray

City Planning’s predictions as to the outcome of neighborhood rezonings will be put under the microscope if a number of bills sponsored by Council Member Francisco Moya become law.

The bills would require city agencies to review past neighborhood rezonings to see how accurate City Planning’s projections were with what took place on the ground in following years.

The bills come at a time when there have been a number of neighborhood rezonings—where existing residents have voiced concern about being displaced due to gentrification– and instances where City Planning’s projections have been found to be way off.

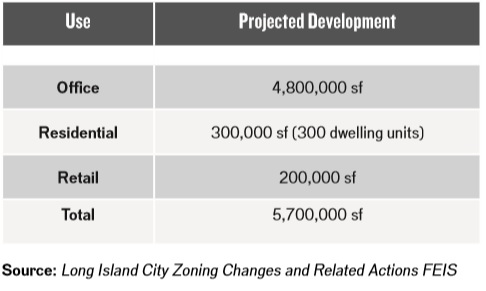

For instance, City Planning’s projections were proven wrong when it rezoned a 37-block area in 2001 in the Court Square/Queens Plaza area. The city anticipated, according to its Environmental Impact Statement in 2001, that no more than 300 residential units would be built in the rezoned area by 2010, according to a report released by The Municipal Art Society of New York last year. In 2010, there were 800 residential units and by 2018 almost 10,000 units—with more coming.

With each neighborhood rezoning, the city goes through an environment review process, called the City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR), to identify the likely outcome.

Based on the CEQR manual, the city must evaluate the impact of a rezoning on land use, traffic, air quality, open space, schools, socioeconomics, among other items. City Planning studies these impacts and makes projections that go into an Environmental Impact Statement, which the public relies on when it undergoes the ULURP public review process.

City Planning works with other city agencies, such as the School Construction Authority, Department of Transportation and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development, to produce an Environmental Impact Statement. The agencies provide guidance based on City Planning’s calculations.

However, the city is not held accountable for its predictions and legislators want that to change. There is no mandate requiring officials to re-examine their projections.

City Planning Projection for 2010 following LIC rezoning, according to Final Environmental Impact Statement (RWCS). City Planning anticipated an office boom. Source: Municipal Arts Society report.

Several legislators want the city to study past rezonings to find out what the outcome was and make changes to the CEQR manual and process if needed.

Council Member Francisco Moya–who represents the 21st Council District covering East Elmhurst, Corona, and Lefrak City–said the city lacks data of what transpired through past rezonings that would be helpful to residents of neighborhoods that will be rezoned.

He said that people are concerned when the city eyes up their area for a rezoning, wary that they are going to be forced out by higher rents as new development inevitably follows. Other concerns deal with school overcrowding and the lack of public space.

Council Member Francisco Moya (Source: Facebook)

Legislators have put forward four bills that would require the city to study the impacts of a neighborhood rezoning on secondary displacement, school overcrowding and transportation—and compare them to the predictions that were in the Environmental Impact Statement.

If the predictions are off, the city would be required to make adjustments to the CEQR manual that guides the process to increase the likelihood that they are more accurate in future rezonings.

Moya is the sponsor of two of the four bills that have been introduced. One of Moya’s bills would require the city to study each neighborhood five years after it is rezoned to see its impact on secondary displacement of existing residents.

If its projections are off in the Environmental Impact Statement by more than 5 percent as to secondary displacement, City Planning would have to make recommendations as to how CEQR can be improved so projections in future neighborhood rezonings are more accurate.

The bill, which is currently in the Land Use committee, has 21 co-sponsors.

The second Moya bill would require the city to review the impact on public school capacity four years and 10 years after a rezoning, compared to the projections of the Environmental Impact Statement at the time. If there is a significant discrepancy, City Planning would have to recommend ways it could amend the CEQR manual to improve its future projections.

A third bill, which mirrors Moya’s public-school component, would require an evaluation of the impact of a rezoning on transportation.

The fourth bill would monitor the commitments that the city made to a neighborhood during a rezoning to ensure that any predicted problems are mitigated. The bill would track the progress of those commitments.

The City defends the process as it stands today and is reluctant to spend its resources studying the outcome. It argues that the Environmental Impact Statement is based on the best information it has at the time.

“Environmental review looks at possible development, and discloses the potential impacts. This is based on data and knowledge of conditions and trends at the time. Beyond that, the outcome of a rezoning is heavily influenced by real-world events, such as an economic recession or a boom,” said a spokesperson for City Planning.

City agencies such as the Department of Transportation, the School Construction Authority and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) would be tasked with studying where things stand today if these bills were to become law.

Representatives of these agencies question whether such labor-intensive studies would result in any meaningful changes.

Susan Amron, the general counsel at the Department of City Planning, told the Council’s Land Use committee during a hearing on the bills last week that it was too simplistic to place residential displacement strictly on rezonings.

The issue of displacement, Amron said, is a citywide challenge, with rents rising inside and outside of rezoned areas and there are a number of factors as to why. “To focus solely on rezoning as the driver of neighborhood change misses the complex reality of New York city’s population dynamics, and treats neighborhoods as static places.”

She added that even with perfect data, there are changes that can’t be predicted. For example, “Past traffic analyses could not have predicted the rise of for-hire vehicles such as Uber or Lyft.”

Legislators then questioned the value of the Environmental Impact Statements and said they should still be reviewed years late.

“How can you expect us to trust your reports when you’re not fact checking or double checking your recommendations?” said Rafael Salamanca, at the hearing who represents the south east Bronx and is the chair of the Land Use Committee.

Moya said that the City Planning should be held accountable for its projections and that its unwilling to take any responsibility or look at how they can be improved.

“We are only asking for a study and we have an opportunity to do better and we should do better,” Moya said. “I think this is a no brainer.”